Similar to other holidays, Halloween brings with it a number of intellectual property concerns. This is unsurprising as Halloween propagates a large amount of creative energy and spans almost every area of intellectual property law.

When one thinks “Halloween” perhaps the first thing to come to mind is the classic jack-o’-lantern, featuring a carved face in an evacuated pumpkin, turnip, or other root vegetable. In 1889, a jack-a-lantern was patented for a device capable of providing amusement for children and which can also be used as a campaign torch for celebrations, torch-light processions, political meetings, and “other like occasions where an effective pyrotechnic display is desirable.” Indeed, U.S. Patent No. 396,252 issued to George Beidler for a lantern, constructed of sheet metal, papier-mache, glass or other material, in which eyes, nostrils, and a mouth are stamped or otherwise represented so as to allow a candlestick displaced therein to show through.

Roughly one-hundred years after Mr. Beidler patented the jack-a-lantern, the first pumpkin carving kit was patented and aptly called the “carve-o-lantern kit.” This patent discloses not only different types of cutting tools for penetration of “the fleshy shell of a pumpkin” but also an instruction book which provides various patterns and decorative designs to be used on the pumpkin. Interestingly, the assignee of this invention, Pumpkin Masters, used its patent to sue more than fifty retailers and manufacturers for allegedly infringing its patented kit. Big name defendants included Williams-Sonoma Inc., Walt Disney Co., and Restoration Hardware. Most of these suits settled but Pumpkin Masters continued to maintain its position that it “changed the way America carves its gourds with unique scooping and cutting tools that allow for elaborate design.”

As most children would likely agree, there can be no Halloween without candy and there can be no candy without a means of carrying it. As such, U.S. Patent No. 6,629,810 issued in 2003 for a “Halloween treat carrier.” The carrier essentially features a container having a Halloween design and a glow-in-the-dark material.

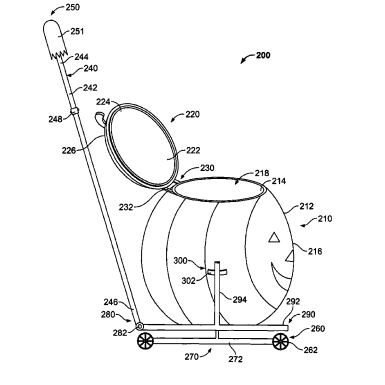

Another pumpkin-y treat carrier, a “Halloween portable container,” appears to be a jack-o’-lantern on wheels capable of carrying treats collected during trick-or-treating. U.S. Patent No. 7,594,669 to Linda Acosta confirms the invention comprises a rolling container contemplated to be in the form of a pumpkin, witch, ghost, goblin, monster, vampire, werewolf, or any other Halloween related object, and having a cover, as well as, an arm or rod to assist in the maneuvering, driving, or controlling of the apparatus. This rolling trick-or-treat container solved the difficult task faced by many children of having to carry a heavy sack of confections, which generally does not have a lid to prevent spillage and unwanted spoilage of said confections.

Candy companies have not hesitated in capitalizing on Halloween by taking advantage of the intellectual property system in protecting their various confections. The popular candy corn, commonly associated with the holiday and the fall season, was trademarked in 1997. The Goelitz Confectionary Company, now known as the Jelly Belly Company, applied for and received registration for “The Original Gourmet Candy Corn.”

As another example, since 1906, The Hershey Company has held the trademark for “Hershey’s.” Additionally, Hershey owns trademark for the design of Hershey’s Kisses as well as the term “kisses.” Moreover, Hershey was initially denied registration for “kiss” due to the term constituting the generic word for that type of candy. The Hershey Company commissioned a survey of potential candy buyers, to whom the difference between a brand name and a generic name was explained and who were asked whether kisses (in addition to other names such as M&M’s and malted milk balls) were generic or brands. Due to the survey’s overwhelming results indicating that consumers understood “kiss” to emanate from Hershey, the Appeals Court sided with Hershey, allowing the company to trademark the word.

Finally, costumes have continued to generate a decent amount of litigation, most of which has been copyright-based. Indeed, in 1991, the Copyright Office used a Policy Decision on the Registrability of Costume Designs, providing that fanciful costumes were to be treated as useful articles and therefore, were generally not subject to copyright protection. This decision effectively defined costumes under the useful article doctrine, which provides that useful articles are those with an intrinsic utilitarian function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or convey information. As such, “useful articles” are not copyrightable. Costumes serve a dual utilitarian purpose as both clothing and also as masquerading.

Masks, on the other hand, are not useful articles and may qualify for copyright protection. That being said, masks, as with all other works, must still meet basic copyrightability requirements, such as the requirement that the mask be original. In one instance, the creator of the mask that was used for Michael Myers brought suit against the makers of the Halloween movie franchise for copyright infringement. The mask-maker ultimately lost because the Court determined the mask was merely a mold of actor William Shatner’s head, originally formed for a Captain Kirk mask, and therefore was not sufficiently original to warrant protection.