What do trademark lawyers do?

Trademark law involves the protection of brand names, logos, designs, and trade dress applied to goods and services. Trademark attorneys, like those at Omni Legal Group, provide legal advice on trademark matters and assist clients in all stages of the trademark process. Unlike patent attorneys, trademark attorneys need not have passed any specialized registration examination before the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). Rather, trademark attorneys need only be active members in good standing of the bar of the highest court of any State. Trademark lawyers’ jobs include both transactional and litigation aspects.

When a new trademark is contemplated for registration, one key function of a trademark lawyer is to determine that the proposed mark qualifies for protection and does not infringe another’s rights. In order to do so, the lawyer may perform a trademark search of the USPTO database and other available records for confusingly similar registered marks. Indeed, all information submitted to the USPTO at any point during the trademark application and/or registration process is public record so even if a mere application has been filed for a mark, the USPTO database will indicate the same. If the attorney finds a conflicting mark, the client will potentially be denied registration and may even be subject to a lawsuit by the registered owner of the existing mark. In this way, trademark lawyers assess the chances of success of an application. Thus, trademark attorneys’ role in advising on adoption and selection of a new trademark can save time and resources down the road.

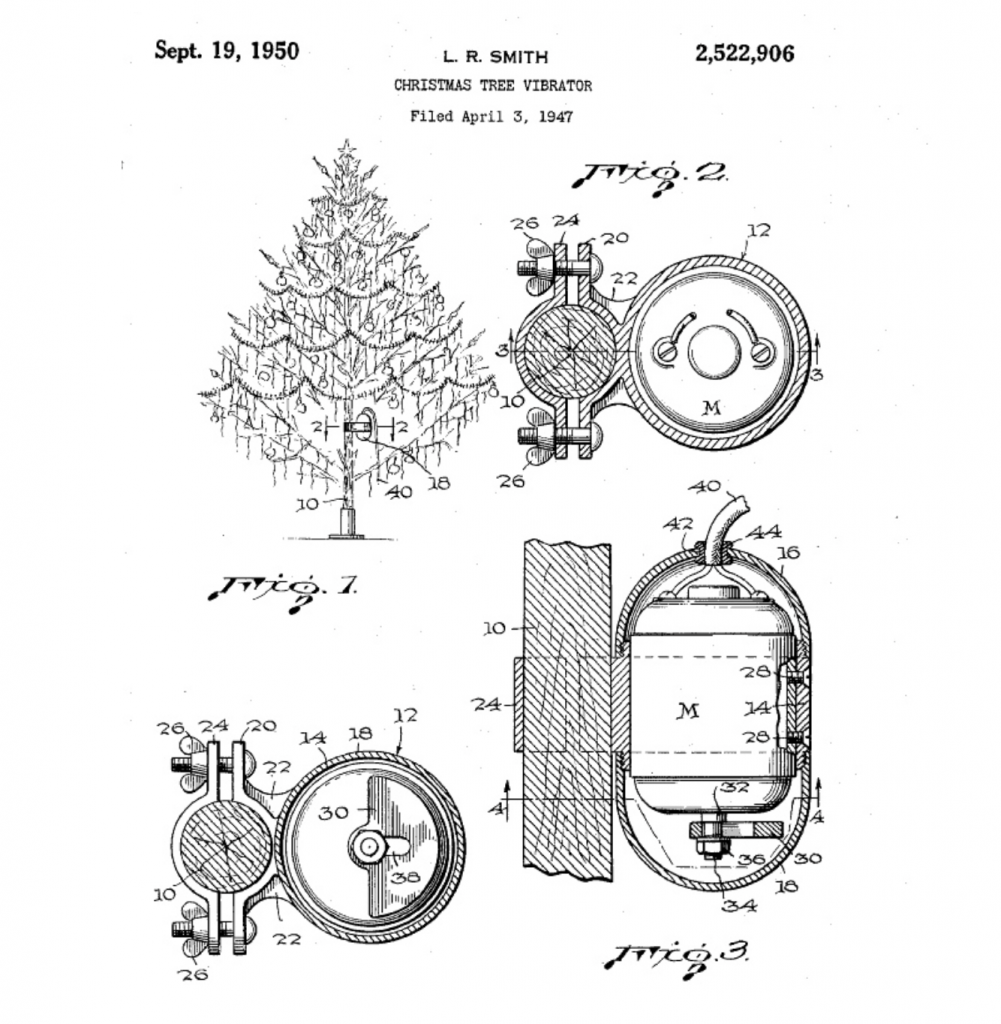

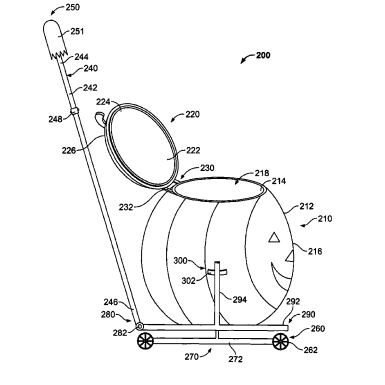

After the trademark clearance has been performed, the trademark lawyer may also file and prosecute the trademark application. Initially, this entails preparing the application forms, including an online form through the Trademark Electronic Application System, the applicable fee, and, if the mark is already in use by the client, the specimen showing such commercial use. If the trademark has not previously been used by the client, the trademark attorney will file what is known as an intent-to-use, or Section 1(b), application, indicating the client has a bona fide intent to use the trademark in commerce. Prior to registration of the mark, it must be demonstrated that the mark is actually being used in commerce.

Not all trademark applications result in registrations. After the USPTO determines that the application meets the minimum filing requirements, a serial number will be assigned and the application forwarded to an examining attorney. The USPTO examining attorney reviews the application and checks its compliance with applicable rules and statutes, such as that mentioned before with regard to likelihood of confusion with an existing mark. If the examining attorney decides that a mark does not deserve registration, an Office Action is issued which explains any substantive, technical, or procedural reasons for refusal. Trademark attorneys are skilled at identifying such issues and responding accordingly, including submitting arguments against substantive refusals and correcting technical or procedural deficiencies.

Once a trademark has been registered, the owner of the mark may still face legal issues in relation thereto. On the one hand, a third party may come forward and claim superior rights to the registered trademark and may oppose registration or seek cancellation of the mark. In such a scenario, the trademark attorney may defend the registrant before the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board or in District Court in proving the mark’s validity and the client’s rights. On the other hand, a third party may begin infringing the trademark owner’s rights by utilizing a mark that is likely to cause consumers to believe there exists an association between the trademark owner and the third party. In this case, the trademark attorney may bring a lawsuit on behalf of the trademark owner to stop the third party’s infringement and ideally obtain monetary relief representing harm suffered by the client.

It is important to note that some trademark attorneys limit their practice strictly to prosecution while others are solely litigators. Here, at Omni Legal Group, our skilled attorneys handle the entire gambit of trademark issues from clearance to prosecution to litigation and have the experience to find the proper solution for your trademark needs.

Read More